What Is a Theory of Action? An Educator’s Guide to Using This Tool for School Improvement

As a coach working alongside school and district leaders every day, I’ve seen how critical it is to have a clear strategy that connects actions to outcomes. School leaders often come to us feeling overwhelmed—pulled in many directions, navigating limited time and resources, and trying to make decisions that will improve outcomes for students. This is where the concept of a Theory of Action becomes so powerful—it provides a clear, intentional roadmap to drive the changes that matter most.

What is a Theory of Action in Education?

A Theory of Action is a clear, intentional annual plan that connects the specific changes a school or district makes to the outcomes they want to achieve. Think of it as a roadmap that articulates the connection between Leadership, Adult Learning, the Instructional Program, and desired improvements in student learning. This roadmap will include:

What actions we believe will lead to improvement

Why those actions are the right ones to take

How those actions will address the core challenges we’re facing

A Theory of Action helps leaders focus on the most critical areas for growth—whether that’s integrating a new high quality curriculum, studying and refining the most effective supports for multilingual learners, or implementing project based learning. It surfaces the why behind decisions and aligns resources like professional development, coaching, and collaboration time to support meaningful, measurable change.

For example, a school’s Theory of Action might look like this:

“If we provide teachers with focused professional development on scaffolding strategies for multilingual learners, and create dedicated collaboration time for lesson planning, then we will see improved student outcomes and increased reclassification rates for our multilingual learner population.”

Our mantra at Partners is that a Theory of Action is a “living document.” Its power lies in creating it with the community that’s doing the work and making it a part of daily conversation. It shouldn’t collect dust—it should be taken down from the wall at least once a quarter to reflect on whether the plan is being implemented. And if it is, is it leading to the improvements you hoped for? If not, it’s time to make adjustments.

A well-crafted Theory of Action clarifies priorities, aligns teams, and helps everyone—from superintendents to teachers—understand why the work matters and how it will lead to better outcomes for students.

Why is a Theory of Action Important In Education?

Schools are noisy places. I don’t mean literal noise (though anyone who’s walked through a thriving school environment knows that’s true, too). I mean the noise of competing priorities, new policies, urgent challenges, and unexpected crises—all demanding a leader’s attention.

In this environment, it’s easy for efforts to feel disconnected. One initiative targets classroom instruction. Another looks at attendance. A third focuses on professional development. Each one might be valuable, but if they aren’t connected to a shared purpose and grounded in the real issues holding back progress, they won’t produce the results we’re all striving for.

That’s why developing a Theory of Action (ToA) is so important. It helps leaders step back, identify root causes, and focus their energy on the changes that matter most. It brings to the surface and makes actionable the ideas that leaders hold in their heads, so that the broader community can work in alignment toward shared goals and hypotheses on how to achieve them.

Another benefit of the process and the tool is that it is specific to school systems. It doesn’t allow a leadership team to stop at what they believe they need to improve in their instructional program; they must also articulate how they will leverage their professional learning systems to make instructional shifts and then study their impact. This ensures that schools create actionable plans that are both strategic and grounded in continuous improvement.

Over the years I have seen many schools adopt the routine of developing an annual theory of action. At first, teams are often willing to give it a try but they are worried that it is just another accountability tool that will go on the shelf and be forgotten. Within a couple years however, I notice that it easily becomes an important part of their planning and progress monitoring routine.

How to Develop a Theory of Action

Start With Root Causes

Before we can create a Theory of Action, we have to start by uncovering the root causes of a school or district’s challenges.

For example, a school’s challenge might not just be that students are struggling academically—it might be that professional learning systems aren’t effectively equipping teachers with the tools they need to support those students. The Partners process emphasizes looking beyond surface-level problems to find systemic barriers and gaps that hold back progress.

In this step, it’s important to focus on one challenge and ask questions like:

What data do we have? What is it telling us?

What’s really driving the challenges we’re seeing?

What assumptions are we making? Whose voices and perspectives are missing?

Where are we already strong? What stories of success could we study?

What gaps need to be addressed?

Uncovering root causes often requires rethinking how we collect and use data. Traditional approaches may overlook systemic inequities, but with an equity lens data can be a powerful tool for change. I invite you to take our free, self-paced Data for Liberation course to learn more about how to transform your approach to data.

All in all, get creative and scrappy with how you weave in time for root cause analysis questions. You might have it be part of an existing team meeting, restructure how protocols are run, or something else.

Remember, this part of the process isn’t about blame. It’s about clarity—getting a full picture of what’s happening so we can take intentional, aligned action.

Defining Your Theory of Action

Once root causes are identified, we work together to build a Theory of Action: a focused statement of the changes that leaders believe will make the biggest difference.

But narrowing down those changes isn’t always easy. One of the biggest challenges I’ve seen school leaders face is balancing the desire to lead large-scale improvements across instructional programs—because the kids need them now—with the understanding that real improvement requires focus and follow-through. The key is finding the right balance between ambitious goals and what’s truly manageable.

I recently worked with a Bay Area district to make some tough decisions about where to focus their efforts in the year ahead. One of the district leaders suggested a simple yet effective approach: drawing a dotted line. We wrote each potential focus area on a Post-it note, then worked together to decide how many priorities they could truly accomplish with our support in one year.

We moved the Post-it notes around, testing different combinations, and agreed that anything below the dotted line wouldn’t get the time or attention for the year. This process helped make sure their Theory of Action stayed focused and achievable.

With this in mind, let’s look at what a strong Theory of Action should include to guide meaningful change:

SMART- E (Specific Measurable Achievable Relevant Timebound and Equitable) goals

A hypothesis about what practices and research-based strategies will lead to change.

A plan for professional learning that will support and equip teachers with what they need to achieve goals.

(Note: Scroll down below to see an example of a Theory of Action)

This kind of clarity gives schools direction and helps ensure school leaders align their resources—collaboration time, coaching support, professional development budgets—around a shared vision for improvement.

Another note I’d like to add is that a Theory of Action (ToA) is also highly adaptable, allowing schools to use it in ways that work for their unique needs. For example, one middle school I worked with in San Francisco Unified became so familiar with the process that each academic department created its own Theory of Action. These departmental ToAs aligned with the school-wide version, creating a unified vision while allowing each team to focus on goals specific to their work.

This demonstrates how schools can use a ToA flexibly to address overall priorities while breaking them down into actionable plans at every level of the organization.

Going From Theory of Action to Real Results

Of course, a Theory of Action is only the beginning. To bring it to life, we help leaders develop clear, actionable plans that outline the steps they’ll take, who will lead them, and how progress will be measured.

This includes:

Developing a professional learning scope and sequence that connects directly to the Theory of Action.

Encouraging leadership teams to review their Theory of Action at least quarterly, reflecting on whether it’s being implemented effectively and driving measurable improvements.

Setting up systems to track progress and celebrate successes along the way.

We encourage a visual design of a Theory of Action that will resonate with the school community—whether that means adding more detail or simplifying further.

When leaders have this kind of focus, it changes everything. Instead of feeling pulled in a hundred directions, they can lead with confidence—knowing their energy is going to the work that will make the biggest difference for students.

Theory of Action Example

If you remember earlier, I mentioned that a Theory of Action is usually an annual plan. However, it’s important to remember that a Theory of Action is a hypothesis–it’s meant to evolve as a school reflects on what’s working and where adjustments are needed.

At Partners, we often guide school or district leaders in creating an annual theory of action that lays out overarching goals and priorities for the school year. From there, we support school leaders with guiding their teams to break down the annual Theory of Action into smaller, manageable 6-week cycles. These shorter cycles allow educators to test their hypotheses, gather evidence, and make adjustments in real time instead of waiting until the end of the year.

Here’s an example of how this approach can play out:

Below, you can see an annual Theory of Action (ToA) that’s focused on improving student engagement and academic outcomes in ELA by creating space for teacher collaboration, implementing relevant professional development, and creating a culture of affirmation and celebration. Note that this ToA is a more condensed version of this example.

Image description: An example of an annual Theory of Action (ToA) that a school or district could use to highlight their overarching priorities in professional learning, instructional moves, and student learning goals. This ToA is focused on improving student outcomes in ELA on The Smarter Balanced Consortium (SBAC).

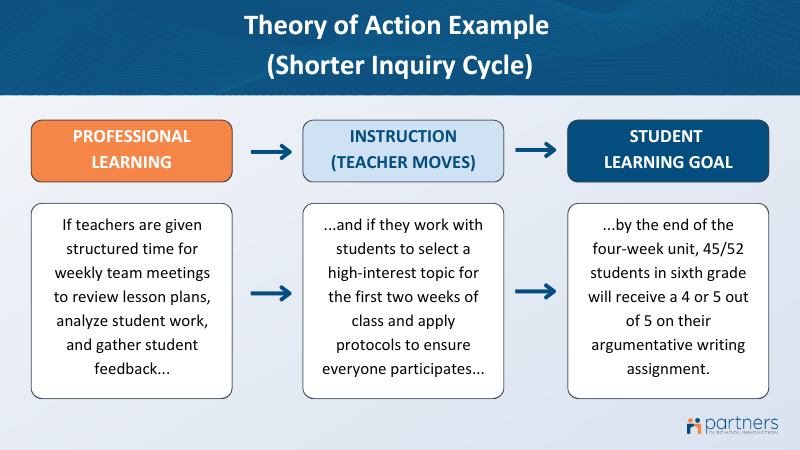

Within this broader plan, a team of six-grade ELA teachers might conduct a six-week inquiry cycle specifically targeting argumentative writing. Anchored to the annual Theory of Action, their hypothesis might be:

“If we have structured weekly collaboration time to analyze student work and gather student feedback, and if we work with students to select high-interest writing topics and apply inclusive discussion protocols, then we’ll see improved engagement and more proficiency in argumentative writing.”

Image description: This is an example of a six-week inquiry cycle that is anchored to the year-long Theory of Action outlined earlier. It breaks down how focused teacher professional learning, teacher collaboration time, and instructional moves will be used to drive performance toward student learning goals.

During this cycle, the goal is measurable: By the end of the unit, 45/52 students will score a 4 or 5 on their argumentative writing assignments. The data collected during this short-term cycle is closely aligned to the larger Theory of Action, allowing the team to test strategies, gather reflections on what’s working, and adjust before scaling or shifting focus to a new cycle.

If you’re interested in learning how to use data more effectively in your improvement cycles, our Leading Improvement Cycles course provides a practical guide on how to close opportunity gaps, and measure progress towards your goals.

At its core, this process begins with school leaders and their communities identifying student learning goals that address a specific need or area for improvement. This includes defining a set of instructional shifts–like changes to curriculum, instruction, assessment, or school culture– that they believe will help them progress towards meeting student learning goals. Alongside these shifts, leaders develop clear plans for professional learning spaces where collaboration, reflection, and adjustments can happen. Try It Out with Our Theory of Action Template

To help you get started, we’ve created a Theory of Action Guide with templates and additional examples. Use it to craft your own strategies, collaborate with your team, and track progress toward your goals. See the guide here.

One clear benefit of the Partners theory of action template is that it fits on a single page. Many schools have a 20+ page school improvement plan that they submit to the state, but a theory of action helps synthesize the content of that plan into a single document that everyone can engage with.

Interested in Partnering With Us?

If your school or district is feeling overwhelmed by competing priorities, you’re not alone. If you're interested in learning more about how Partners in School Innovation can support you with building the systems and strategies needed to bring your vision to life, contact us today.

About Amanda Bachelor

Since 2011, Amanda Bachelor has supported schools and districts through Partners in School Innovation and currently serves as the organization’s Director of Program Design and Development. She loves the opportunity to work side by side with teachers and leaders all over the Bay Area including Alum Rock, Oak Grove, West Contra Costa, Emeryville, San Francisco Unified, and South San Francisco.

Amanda is passionate about listening deeply to the context in which educators are operating and paving a path to improvement that is both ambitious and realistic. She began her career as a bilingual elementary school teacher in East Harlem in New York City and then spent years launching a leadership program for Aboriginal Youth in the remote north of Ontario. Under all circumstances, she remains committed to designing joyful, rigorous, and relevant learning experiences for our most marginalized students.

Amanda lives in Half Moon Bay and spends weekends having outdoor adventures with her family, including 3-year-old Cole and 5-year-old Alex. In the fall, you will find the family biking up and down the coastal trail avoiding pumpkin traffic. In the winter, you can find them on I-80 to and from Tahoe trying to get precious family time on the ski slopes.